“It is like reconstructing the whole of Paris from Lego bricks. It’s about three-quarters-of-a-million small decisions. It’s not about who will live and who will die and who will go to bed with whom. Those are the easy ones. It’s about choosing adjectives and adverbs and punctuation. These are molecular decisions that you have to take and nobody will appreciate, for the same reason that nobody ever pays attention to a single note in a symphony in a concert hall, except when the note is false. So you have to work every hard in order for your readers not to note a single false note. That is the business of three-quarters-of-a-million decisions.”

See that quote above? (I know that I start a lot of posts with quotes and you skip over them. But please go back and take a second to read this one. We’ll wait til you get back…)

Okay, that quote is by the writer Amos Oz, and I have kept it around because whenever I get in the weeds with my writing, it’s helpful to read it and be reminded that creating a book is really nothing but a a very long series of decisions. (Click here to read the whole interview with Oz. It’s worth a detour later.)

Decisions, decisions…

We make thousands of them every day, and they run the gamut from the semi-conscious to the life-altering. Get up or hit the snooze button? Walk the dog now or hope he makes it until I get home? Buy or rent? Change jobs or roll the dice and go back to school? Call up the ex-wife and tell her the truth? Send my son to rehab? Confront mom about giving up her car keys?

Since this process is part of our everyday life, you’d think making decisions would be rote when it comes to our writing. But it’s not. Just ask any poor slob who has painted himself into the plot corner and said, “Oh crap, now what?”

Like Amos Oz, I think a good novel is made by careful and calculated decision-making. Not that there isn’t room for serendipity, flights of fancy, and raw passion. Yes, characters take on a life of their own, but we still hold their reins. Yes, we can’t anticipate every detour, but we can keep the car under fifty as we career down the road less written about. When it comes to writing, I really believe in the virtue of control. (Hey, whatcha want? I’m a Scorpio with Virgo rising). So I’d like to talk today about how to make our decision-making more acute.

I just finished critiquing a partial manuscript of an unpublished author (I do this for charity). And while there was good stuff going on, I sensed that the writer wasn’t in control of his decisions. He was like a guy thrown into a swift-moving river and had relinquished his fate to the rapids and rocks instead of making an effort to steer toward a goal. He was letting his plot and characters propel him forward rather than using his craft oars to guide him toward where he really wanted to go.

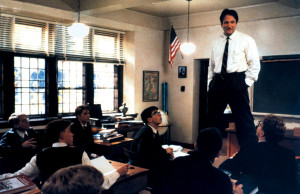

Years ago, I went on a white-water rafting trip on the Nantahala River (where part ofDeliverance was filmed. That’s me middle right in the picture above). It was white-knuckle stuff, but I always had faith that our guide could get us through. He knew where the rocks and whirlpools were, when we needed to pull right, or when we needed to ford a bad stretch. He made decisions.

Okay, enough with the metaphors. Give me a rock I can grab onto, I hear you saying. So let’s try to break down the big decisions you need to make that can make or break your book.

1. Where do I start?

We crime dogs get drilled into us that a fast break from the gate is vital to mystery and thrillers, and while I believe you can risk a slow opening if it is well done, I think your POINT OF ENTRY is the single most important decision you make. Yes, the opening must be compelling and hint at what’s to come. But enter too early and you risk throat-clearing. (Detective awakened by phone call in night summoning him to crime scene. Ho-hum). Too late and you risk confusion. (What the heck is going on here? Who are these people? Where am I in time and place?).

Let’s take a look at one opening. It’s a little long but worth dissecting:

Dawn broke over Peachtree Street. The sun razored open the downtown corridor, slicing past the construction cranes waiting to dip into the earth and pull up skyscrapers, hotels, convention centers. Frost spiderwebbed across the parks. Fog drifted through the streets. Trees slowly straightened their spines. The wet, ripe meat of the city lurched toward the November light.The only sound was footsteps. Heavy slaps echoed between the buildings as Jimmy Lawson’s police-issue boots pounded the pavement. Sweat poured from his skin. His left knee wanted to give. His body was a symphony of pain. Every muscle was a plucked piano wire. His teeth gritted like a sand block. His heart was a snare drum. The black granite Equitable Building cast a square shadow as he crossed Pryor Street. How many blocks had Jimmy gone? How many more did he have to go?Don Wesley was thrown over his shoulder like a sack of flour. Fire-man’s carry. Harder than it looked. Jimmy’s shoulder was ablaze. His spine drilled into his tailbone. His arm trembled from the effort of keeping Don’s legs clamped to his chest. The man could already be dead. He wasn’t moving. His head tapped into the small of Jimmy’s back as he barreled down Edgewood faster than he’d ever carried the ball down the field. He didn’t know if it was Don’s blood or his own sweat that was rolling down the back of his legs, pooling into his boots.He wouldn’t survive this. There was no way a man could survive this.

This is from Karin Slaughter’s lastest, Cop Town. Why do I like this opening? Because even though she uses a lot of description, the effect is visceral and immediate. She could have started with the shooting incident itself, but haven’t we all read that a million times? No, she dives into the bleeding heart of the scene by showing a cop carrying his dying partner. What is left UNSAID is compelling and makes us want to read on: What happened? Why didn’t he just get in his squad car and drive? Where is he going? Are both men shot? Turns out, Jimmy carries his partner to the hospital but does he survive? You have to read on…you just have to. Cop Town is up for the Best Novel Edgar this year, by the way.

2. Whose story is this?

Every story needs a protagonist. That much we all know. But sometimes, in the hurly-burly of writing, we can lose sight of who owns the story. The result can be that seductive secondary characters take over, or the villain (whom we all love to lavish our attention on) becomes hyper-vivid. The protag-hero is, to my mind, the hardest character to create because you must invest so much of the story’s logic and impact in him that he can mutate from calm center to sidelined cipher.

Sometimes, you might start out telling the story from one character’s POV, believing he is your hero, but then a second character elbows into the spotlight. This happened to me with my current book. I opened with a woman waking up in a hospital with concussion-induced amnesia and she has a gut-punch fear that her husband tried to kill her. So she bolts from the hospital and goes on the run. She’s my unreliable narrator protag, I thought. Until her husband hires a skip tracer to bring her home. It took fifty-some pages before I realized I had a full-scale dual-protag story on my hands.

Now this is not to say you can’t have a teeming cast in your story. I’m still slogging through Ken Follett’s The Pillars of the Earth. Early on, I was captivated by the protag Tom Builder, but whenever Follett moved away from Tom, I got impatient. Later in this massive book, the protag spotlight shifts to his step-son Jack. I missed Tom badly.

Don’t confuse point of view shift with protagonist. A book can have numerous POV’s, but the STORY’S ARC is usually best tethered to one character’s journey. The Lord of the Rings is a sprawling saga with at least three major heroic types. But isn’t Frodo the true protag? (Not sure…throwing it out for discussion).

And be careful about setting up a false or “decoy” protag. This is a character that dominates so much of a book in its early going, that the reader begins to identify with her and invest in her journey. But then this character is marginalized (usually killed). Think of Marion Crane in Psycho, who dominated the movie for 47 minutes until Norman Bates stepped out of the shadows to become the putative protag. It could be argued that Stieg Larsson’s Mikael Blomkvist is a decoy protag, because while most the plot’s machinery is built around him, Lizabeth Salander is the true action hero and embodiment of the story’s themes. At the very least, I’d consider them dual protags.

A word about unreliable narrators and dual protags: Neither is easy to pull off. Believe me, I know — now. Being in the POV of an unreliable narrator is exhausting for the writer and can, consequently, tire the reader as well. As for dual protags, you the writer will tend to bond more strongly with one over the other. So will your readers. Unless you are confident of bringing two equal beings to life, stay with one protag. You don’t want your reader saying, “Gee, I wish Tom the Builder would come back.”

Don’t juggle with chain saws until you’ve mastered machetes.

3. What am I trying to say?

We’ve had great posts here on the subject of theme. I’m going out on limb here and say all good books have themes. Yes, your goal might be modest — you just want to entertain readers. (Don’t we all?) But beneath the grinding gears of plot, even light books can have something to say about the human condition. A romance might be “about” how love is doomed without trust. A courtroom drama might be “about” the morality of the death penalty. Good fiction, Stephen King says, “always begins with story and progresses to theme.” And often, you don’t even grasp the theme until later in the book or even during rewrites.

Last week, our new publisher sent us a long questionnaire. They wanted our ideas on cover design, colors, typography, who we thought our audience was, and whose books are similar to ours. They also asked us to write our own back copy. Not because they wanted us to do their job; they wanted us to be able to articulate the essence of our story. And I tell you, if you can’t write your own back copy (about two paragraphs), you might not have a grip on your story and what it is about.

They also asked us some other pointed questions: What are your major and minor conflicts? What is the book’s theme(s)? What are the recurring visual motifs or symbols? What is the book’s tone and mood? Which leads me to…

4. What mood am I in?

My publisher’s questionnaire listed some “mood” words to help us: haunting, witty, intense, sweet, hopeful, psychological, somber, epic, tragic, foreboding, romantic. They were asking us this because they want the design and promotion to enhance our chances for success in a cacophonous book market. You, too, have to think about this as you write your book, whether you self-pub or go traditional. What kind of world are you asking your reader to enter? How do you want them to feel? Once you can answer this question, you then must use all your powers and craft to create what Edgar Allan Poe called “Unity of Effect.” Every word and image, Poe believed, had to be carefully chosen to illicit an emotion. In his short stories, it was fear, of course. In his poems, you could argue, he was going for melancholy. What are you aiming for?

5. Where am I?

Don’t neglect your setting. I know…that’s stating the obvious. But I’m often surprised at how paltry setting is rendered in crime fiction. We need to know where we are very early in the story, preferably inserted gracefully into the narrative flow via sharp description. Yeah, you can slap one of those tags at the beginning of chapter one — Somewhere in the Gobi Desert, Sept, 1904. I concede that you need signposts at times; I’ve used them myself. But they can be a crutch. As a reader, I prefer to be parachuted into a place and use my senses rather than have the writer stick a sign in my face. Here’s a nice free-fall:

Exmoor dripped with dirty bracken, rough, colorless grass, prickly gorse, and last year’s heather, so black it looked as if wet fire had swept across the landscape, taking the trees with it and leaving the moor cold and exposed to face the winter unprotected.

That’s Belinda Bauer opening her thriller Black Lands. Now I don’t have the foggiest where “Exmoor” is, but I have a pretty good notion it’s a dark place somewhere up by England where bad stuff happens.

6. Am I doing this for me or for the story?

The story always has to come first. You can’t kill someone off just because you’ve stalled in the middle and you’re desperate. You can’t let a character hog the story just because you’ve fallen in love with her or she’s easier to write than your protag. You can’t add a twist just because you think it will make you look clever. All twists must be organic, emerging from the plot, not from your “hey-watch-this!” writer ego. Go back to question 2: Whose story it is? Well, it’s not yours; it’s your characters’s. It’s not about you using fancy words or filigreed metaphors. It’s not about you trying to transcend the genre, win some award, or anything else. It’s about the people in your book.

As Elmore Leonard once said, “Always write from a character’s point of view. Write in their language to keep the sense that it’s their story. They’re the most important thing.”

This one is dear to me because my collaborator-sister Kelly and I sometimes have two distinct ideas of where a story might be going or what a character is like. We’re often asked if we argue. No, we don’t. Because we know that our egos don’t matter; only the story does.

7. Does this make sense?

As I typed that headline above, I started hearing Olivia Newton John: “Let’s get logical, logical! I wanna get logical! Let me hear you characters talk! Let me see your story walk!” So my last question here is a plea for simple clarity in three things: your writing style, plot structure, and character motivation. Let’s break them down:

Writing style: Don’t confuse your readers. Chose the simplest but most evocative words you can find. As Stephen King says, “One of the really bad things you can do to your writing is dressing up the vocabulary, looking for long words because maybe you’re a little ashamed of your short ones.” In other words, most the time a lawn is just a lawn, not a verdant sward.

Be clear in your directions when you move your characters through time and space. If someone enters a room, tell us. If you jump ahead three days in time, tell us. This is the “busy work” of fiction writing but it’s no less important. If your reader can’t follow the simple physical movements in your story, they will give up on you and your book.

Plot structure: Your story must have a durable thread of logic that runs from beginning to end. Events on your plot arc must emerge organically and not from coincidence. (no deus ex machina or long-lost Uncle Dickie from Australia showing up in chapter 40 to announce he is the killer) Your details of police, legal and medical procedure must ring true. Your twists and turns must be well-planned and hard-earned. Does the plot, as a whole, make sense? And if you write sci-fi, dystopian fiction or horror, does the artificial world you create obey the rules of its own logic and does it FEEL believable?

Character motivation: Man, is this one important. I can’t believe I left it for last. Characters are your lifeblood and if you want the reader to believe in them, to care about them, to root against them or cheer for them, they must be multi-dimensional and “real.” They must conform to their own internal logic. They must be true to their personalities. We’ve all read books where we say, “Shoot, that guy would have never done that!” The writer has not done her job in this case, has not asked herself: “Does this make sense for this person to do this?” This post is running long, so I’m going to advise you to go back and read Jodie’s excellent post yesterday on consistency in characters. As she says, “Don’t impose your preconceived ideas on the character – you risk making him do things he just wouldn’t do. Know your characters really well and the rest will naturally follow.”CLICK HERE TO GO BACK.

Decisions, decisions…

As Amos Oz said in his quote above, nobody ever pays attention to a single note in a symphony in a concert hall, except when the note is false.